The Books I Read in January

A genuine must-read, a complete disappointment and a few in between; we have quite a lot to discuss!

At the end of 2024 I made a list of authors I wanted to read in 2025, I reorganised my shelves so that I’d have at least one shelf of books prioritised, organised and ready to be read, and I made a note of a few books I’d like to reread. It felt like a nice way to start a new year and I genuinely think it has made me feel even more excited about reading.

In January I read two books off the newly organised shelf, re-read a novel and ticked four authors off my list. So, if you want to know how I felt about them all, keep reading!

*The links to the books in this post are Bookshop.org affiliate links. If you purchase through the site I’ll get a small commission at no cost to you.

When We Were Birds by Ayanna Lloyd Banwo.

"... I see you. I see the wrong they do you. I drink your pain till it fill me up, drink your sorrow till it fill me up, drink your joy till it fill me up, drink your death till it fill me up. I taste your flesh, yes you were flesh, I see it yes, I know. I know you have loved, yes I know, I know you have killed, yes I know. I know you were here, yes I know, and you, and you, and you were here. Nothing mark your grave but earth have ways to mark those who come back to her. You are not forgotten, no you are not forgotten..."

When We Were Birds is the debut novel of Trinidadian author, Ayanna Lloyd Banwo and tells the story of the intertwined destinies of Darwin, a young man recently arrived in the sprawling city of Port Angeles and newly employed as a grave-digger, and Yejide who lives in the mysterious old house on the hill. While Darwin harbours hopes that he might find his father who left for the big city in search of work and never returned, up on the hill Yejide’s mother is dying and, upon her death, she will bequeath her daughter a legacy which has been passed down from the generations of women before her: the ability to speak to the dead.

This was my first book of 2025 and, having first read it back in 2022, I was keen to revisit it. This is the kind of book that inevitably loses some of its anticipation with a reread but it was nice to be back in that world and it’s also a highly readable novel that offers much but isn’t excessive in its demands. With that said, I’ve come to the conclusion that I simply have no desire to critique this book in the way I usually would because it is forever tied to a period of loss and grief and I’d get very little pleasure from pulling it apart. I’m convinced that this is a difficult book to dislike but if you have ever been in close proximity to death, or know what it is to lose someone beloved to you, I think it holds a little something special. To me, it is what it is.

The Night Watchman by Louise Erdrich

“…Lastly, if you should ever doubt that a series of dry words in a government document can shatter spirits and demolish lives, let this book erase that doubt. Conversely, if you should be of the conviction that we are powerless to change those dry words, let this book give you heart.”

Set in 1953, The Nightwatchman is primarily told from the perspectives of two characters: Thomas Wazhushk, the nightwatchman at a factory near the Turtle Mountain Reservation and Prominent member of the Chippewa Council, and Pixie ‘Patrice’ Paranteau who works at the factory in an attempt to earn enough money to support her mother and brother, while also dealing with her unpredictable and demanding alcoholic father. Thomas’ story mainly follows his attempts to resist the ‘Emancipation Bill’, yet another attempt by the US government to further diminish the rights of the Native American population, while Pixie’s story focuses on her attempts to find her sister Vera who moved to the city and hasn’t been since.

Inspired by Erdrich’s own family history, I appreciated how this novel illustrates various forms of resistance employed by the Native American people in an attempt to resist colonisation: legal recourse, yes, but also the preservation of language, food, rituals and traditions. These were some of the most moving aspects of this book. There were quite a few characters and strands to keep up with and I get the feeling that Erdrich leans towards creating a cast or community of characters within her stories, which I can appreciate as a way of exploring multiple perspectives and experiences and providing a real sense of people and place, but it does make the text a bit more dense… With that said, I really valued the inclusion of certain perspectives; Vera’s section, for example, feels really important and, while her insights and experiences were harrowing, they also felt wholly necessary.

The Nightwatchman is my first Erdrich and I get the feeling I’ve landed somewhere in the middle: perhaps not the very best of her work but certainly not her weakest, however, when an author writes as well as Erdrich, this isn’t really a criticism so please don’t take it as one.

Violets by Alex Hyde

"The foetuses had been surgically removed, the doctor said. Along with her womb. Violet blinked. One of the other patients shuffled slowly past her bed. And so. There was a pause. You'll understand that you will not be able to bear children, Mrs Hall?"

This was a random find in my local bookshop. The premise intrigued me and it was a bargain so I got it. This novel is set towards the end of the second world war and follows the dual perspectives of two women named Violet: Violet Hall is newly-wed and works in a munitions factory in Birmingham; in the first pages of the novel, experiences a miscarriage and awakes from surgery to find that not only was she was carrying twins but also that she also had to have her womb removed and further pregnancies are no longer an option.

The second Violet- Violet Owen from Wales- is unmarried and unexpectedly pregnant and makes the decision to sign up for war work overseas, opening herself up to a whole host of new experiences, while she figures out what to do. Eventually Violet Owen gives birth and the paths of the two Violets cross.

In between the perspectives of the two Violets is the voice of ‘Pram-boy’, the unborn child who will connect these two women. Something about this voice- both its tone and its inclusion- reminded me of Max Porter so I wasn’t surprised to see that he’d blurbed the novel.

The novel is written in a rhythmic poetic prose that kind of carries you along and it also proved to be quite a quick read but, while it was certainly moving in parts, it wasn’t as emotionally affecting (to me) as I’d assumed it would be.

The novel was inspired by Alex Hyde’s own family history and I did find myself wondering if it would have even more of an impact on someone who sees their own experiences/family history reflected in it. And I don’t just mean experiences of motherhood or loss, but also someone who also feels a real connection to that period of time. Regardless, there is a universality to the experiences of motherhood, maternity, marriage, war, and loss and the novel is a unique look at two women’s journeys to motherhood and the challenges, societal expectations and pressures women face- both then and now.

Waiting for the Waters to Rise by Maryse Condé (translated by Richard Philcox)

"It's a long story. From what Movar tells me it's the same as yours. Or almost. Our lives start off in a different direction, in very different countries. Then they get closer until they are alike and practically merge. It's because this world has become what it's become, crazy, with no bounds or borders. Please be patient and bear with me to the end. I will try to be brief."

Babakar Traore is a Malian doctor (obstetrician) living in Guadeloupe who, at the start of the novel, is summoned to assist the birth of a young woman- a Haitian immigrant. Unfortunately, he arrives too late to save the young woman but, when he sets eyes on the baby, he is overcome with emotion and, lonely as he is and still grieving the loss of his own wife and child- he makes the decision there and then to adopt the baby girl.

The baby, Anaïs, connects him to a young Haitian man, Movar who was known to the baby’s mother, and who convinces Babakar that the child must maintain a connection to her mother’s family and homeland. From here we follow these two men on their journey to Haiti where they encounter a Palestinian man, Fouad. These three men- unlikely, but also highly likely companions- connected by their experiences of war, displacement, loss and grief find themselves on a journey through Haiti, a land where the dead are as alive as the living and where poverty, violence and corruption mark almost every inch of its soil.

The novel explores themes of displacement, war, greed, colonisation and the impact on those caught in the crossfire and haunted by their experiences. I think this novel’s approach is quite unique in its centring of these three men (and a baby) who are each given the opportunity to tell their story and while this could have felt cluttered and clumsy, this wasn’t the case here (although some characters clearly like the sound of their own voice...) I’m undecided as to whether I would’ve wanted to hear more from the women mentioned in the novel because I also appreciate that it’s rare to get the male perspective on the emotional impact of war, imprisonment, grief, loss etc. as opposed to the physical and literal wounds and scars.

Maryse Condé was another author on my list for this year and, similarly to my experience with Louise Erdrich, I get the feeling that I’ve landed somewhere in the middle; I have no major gripes with this book and really enjoyed reading it but I wouldn’t say I was blown away by it either. I have Condé’s novel Crossing the Mangrove on my shelf so I’m intrigued to experience more of her storytelling.

Our Sister Killjoy by Ama Ata Aidoo*

"If anyone had told her that she would want to pass through England because it was her colonial home, she would have laughed. She generally considered herself too smart to exhibit such weaknesses. But to London she had gone anyway, consoling herself all the while that that was the only way to people at home to understand where she had been. Abroad. Overseas. Germany is overseas. The United States is overseas. But England is another thing. What this thing is, has never been clear to anyone..."

Ama Ata Aidoo is another author who has been on my to-read list for quite some time so I was very pleased when Faber offered to send me a copy of their new reissue of Aidoo’s debut novel, Our Sister Killjoy. First published in 1977, it tells the story of Sissie who is leaving Ghana for the first time, heading to Europe on a scholarship (something about young African people experiencing European education...) The reader primarily gains insight into Sissie’s experiences in Germany and London where she encounters whiteness as she’s never seen it before and is, quite frankly, perplexed and unimpressed and feels no need to pretend otherwise. In London, Sissie’s experiences of encountering the West African diaspora are just as perplexing but also pitying. Again, she’s unimpressed.

The novel is a satirical, scathing indictment of colonial legacy and insidious racism in all its guises with the writing itself taking various forms, including prose poetry and an epistolary section. These shifts did cause me to lose my bearings on a couple of occasions but I was easily righted and it did little to interrupt the overall reading experience.

Sissie is so sharp and astute but also incredibly witty and I underlined numerous passages simply because I was so amused by them. If you want to get a sense of Ama Ata Aidoo’s politics and perspective, which absolutely come through in the novel, I’d recommend listening to the interview below.

The Book of Harlan by Bernice L. McFadden

My introduction to Bernice L. McFadden’s work was her novel, Sugar, which I read quite a few years ago now and really enjoyed. I then read the follow-up, This Bitter Earth, which I didn’t enjoy quite as much but still really liked. So, when I saw that The Book of Harlan has an average rating of 4.08 stars on The Storygraph and comes highly recommended by people whose recommendations I (still) trust, I didn’t doubt for a moment that I’d like it. It turns out out I was wrong…

The novel starts off strong- McFadden knows how to write a cast of characters, how to set the scene and place you in it. But as Harlan enters adulthood and one catastrophe after another befalls him, the book just becomes so miserable. Misery is fine but I think that if you’re going to make a character’s life that painful it should feel wholly necessary and its contribution to the plot should be clear.

To briefly summarise: the book opens with the courtship of Harlan’s parents and his birth in Macon, Georgia in 1917. Harlan and his parents eventually move to Harlem, where Harlan becomes a professional musician. When he is offered an opportunity in Montmartre- “The Harlem of Paris”- Harlan and his best friend, Lizard jump at the opportunity (Lizard doesn’t exactly ‘jump’ for reasons that later become clear but he begrudgingly agrees to accompany Harlan). However, soon after their arrival, Paris falls under Nazi occupation and both Harlan and Lizard find themselves captured and taken to Buchenwald concentration camp.

This book covers some incredibly important themes and highlights how many non-Jewish people were the victim of the Holocaust, whether because of race, sexuality, or disability. This section, while harrowing, served a clear purpose and was really well-written. I think where the book fell short of my expectations was McFadden’s attempt to blend the stories of her own ancestors with those of real characters, as well as a questionably redemptive ending that just left me quite dissatisfied. As I said, this book is loved by many and the reviews speak to that but it felt too clunky for me and might have been more effective had some parts just been omitted altogether. If you’ve read this one and have thoughts I’d love to hear them!

Bright Red Fruit by Safia Elhillo

"& it isn't even really religion that governs us though of course some of the aunties & uncles are pious in the expected ways, seen so often at the mosque that i'm not sure they don't sleep there but the religion we practice is the religion of reputation fear of a deity replaced by fear of each other the whispers the rumours the disgrace the brittleness of a family's good name of a family's honour the brittleness of the girls who hold it in our clumsy hands"

Bright Red Fruit is the story of Samira, a young Sudanese-American girl, who has acquired an undeserved reputation within the community. This experience alters her perception of herself as well as those around her and, as a consequence, she soon finds herself in a dangerous situation and one that also risks ruining her reputation within the spoken word poetry scene- a reputation she has actually come to care about.

Like, Safia Elhillo’s earlier novel, Home is Not a Country, Bright Red Fruit is written for a young adult (YA) audience but can undoubtedly be appreciated by an older reader. And I say this as someone who hasn’t been a young adult for quite some time and loved both books.

The novel sees Samira attempting to have the summer of her life with her two best friends, going to parties and exploring the DC poetry world, until a rumour about her reaches the ears of her mother and she finds herself grounded. Isolated at home, Samira finds an online poetry forum where she meets other likeminded souls, however, she also encounters someone whose presence in her life makes her feel loved, admired and appreciated but also places her in more danger than she realises.

I enjoyed this novel a lot. As with her earlier book, the relationship between Samira and the women in her life is central to the story and adds a real tenderness to it. I love books that centre the relationships between women and for Samira, who is being raised by her mother with the support of her mother’s sister, I really appreciated how the relationships between both mother and daughter but also aunt and niece were written.

Safia Elhillo is a brilliant poet, so the novel’s prose and poetry (it contains both) is as absorbing as you’d hope. She perfectly communicates Samira’s naivety, inexperience and limitations, both as a young person with a narrow view of the world but also as a skilled but developing young poet.

This is a novel that explores some really important themes around family, community, and the unbearable weight of expectation. It asks the reader to consider how vulnerable to exploitation young women might be if they are made to feel as though their reputation matters more than their safety - if they’re not made to understand that they will always, always be believed and loved regardless.

Having now read all of Safia Elhillo’s published work (she also has two poetry collections for adults) it’s so nice to be able to confidently recommend them all and I look forward to reading whatever she writes next.

The Quarter: Stories by Naguib Mahfouz (translated by Roger Allen)

"The disaster had happened. Ayousha had run off with

Zienhum, the baker's boy. When the news broke,

fragments scattered all over the quarter. Down every

alleyway, at least one good heart expressed disbelief.

'God help us all! What a disaster for you, Amm

Jumaa, you are a good man!'

The Amm Jumaa in question was Ayousha's father.

Head of the family, he was the father offive strapping

lads. Ayousha, his only daughter, was now fated to

knock him off his pedestal of decency and respect..."The stories in this collection are all set in Cairo’s Gamaliya quarter where, as you might imagine, all sorts is going on at any one time. The stories consider societal expectations, power dynamics, injustice and exploitation and the ways these might present themselves at a microcosmic level: from the young woman who ruins her family’s reputation by running off to marry the baker’s son, the man who marries a woman half his age and suffers the consequences, or the young orphan boy, Nabqa who is compelled to tell the truths of what he knows of various goings on in the quarter.

I definitely appreciated some stories more than others and I do think you have to appreciate short form for this one because some of these stories are incredibly short. This book’s charm really lies in the detail of every day human interactions and I quite enjoyed the touch of magical realism. The overall tone is also quite light which makes it a highly approachable collection.

I’ve been wanting to read Mahfouz’s infamous Cairo Trilogy for some time and, while I wouldn’t say The Quarter is the most incredible collection of stories ever, it really has whet my appetite and I’m now even more excited to read more of his work.

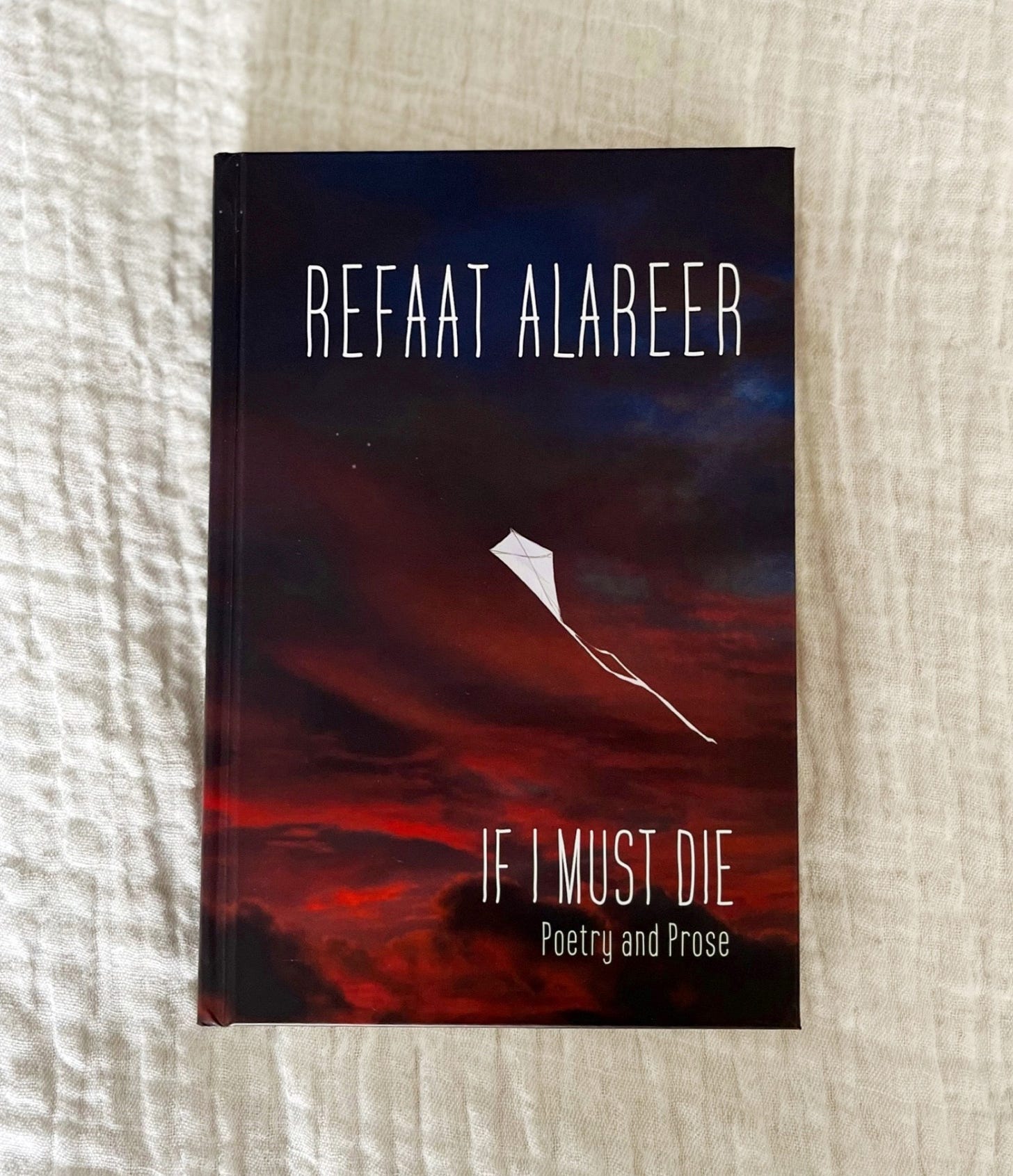

If I Must Die: Poetry and Prose by Refaat Alareer

"I recoil in horror and shudder as I write this – I am exposed, naked, and vulnerable. Reliving the horrors Israel brought on us is one thing, but disclosing your life and your most intimate moments of fear and terror, where you spill your heart out, is another. Sometimes late at night when insomnia hits, I wonder if it is all worth it, if anything will ever change."

Nothing I say about this book- no attempt to describe its importance, its impact on me as a reader, or my experience of reading it will do it justice. If anything, it just emphasises the importance of reading this one for yourself.

The book is predominantly made up of Refaat Alareer’s prose and poetry writings over a period of around ten years, as well as excerpts from various transcribed interviews. The poems, which are interspersed throughout the book, often emphasise or reiterate experiences shared in previous sections and I found this to be incredibly impactful.

Alareer speaks of his experiences growing up under Israeli occupation, the death of his brother who was killed by an Israeli airstrike in 2014, the impact of the numerous wars on his children, and on all the children of Gaza, and the experience of parenting during these aggressions.

He calls out the complicity and negligence of international journalists and the media; he speaks of his childhood and the moments he became aware of the various ways his family history had been marred by the occupation’s brutality, he speaks of the legitimacy of resistance and the importance of education, writing and poetry as forms of resistance. I could go on- there is so much more to be said.

As the book progressed, I knew what was coming; I knew that we’d come to the last of Refaat Alareer’s writing before he and several family members were murdered by an Israeli airstrike on his sister’s home on 6th December 2023. I knew it, and yet I still wasn’t ready for it. This book is an intimate look at how occupation and war impacted every aspect of Refaat’s life- from his birth to his death. To read his words is a privilege I can’t help but feel we are undeserving of, which is why it is even more important that they are read and shared.

And We Live On...

"And another day in Gaza

Another day in Palestine

A day in prison

And we live on

Despite Israel's very much identified flying objects

That we see more than our family and friends

And despite Israel's death sentences

Like lead

Cast upon the head

As we sleep

Like acid rain

Gnawing at our life

Clinging to it like a flea to a kitten

And stuffed in our throats

The moment we say "Amen"

To the prayers of old women and men

Despite Israel's birds of death

Hovering only two meters from our breath

From our dreams and prayers

Blocking their ways to God.

Despite that.

We dream and pray,

Clinging to life even harder

Every time a dear one's life

Is forcibly rooted up.

We live.

We live.

We do."I can’t remember the last time I said a book was a must-read and I generally think it’s a term that is used far too liberally so please believe me when I say that I don’t use it lightly here.

So, those are all the books I read in January. Have you read any of them? Any you’re hoping to read?

February Reading Plans

I don’t usually go into a new month with a firm list of books I want to read simply because my innate instinct is to simply refuse if ever anyone tries to tell me what to do (even if that person is myself). So, as always, this month I intend to just go where my mood takes me but here are a few potentials:

Towards the end of January I started reading Cutting for Stone by Abraham Verghese, which is a book I’ve wanted to read for years but it’s a little chunky so I’ve tended to avoid it. This is the only book I’ve carried over into this month and so far I’m enjoying it.

If you’ve seen my 2025 anticipated reads, you might remember that Omar El Akkad’s latest book, One Day Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This was on the list. The publisher (Canongate) have since sent a copy so I hope to read it soon. Another book I’m hoping to get to is Djinns by Fatma Aydemir (translated by Jon Cho-Polizzi), which sounds brilliant and I’ve yet to hear anyone say otherwise.

But, like I said, I could end up reading all or none of these so you’ll just have to wait until next month to find out…

Until next time,

Tasnim

And if you enjoy reading these posts and you’d ever like to support in some way, you can ‘buy me a coffee’ here. It’s always much appreciated.

I love Louise Erdrich’s books. Her more recent ones are not as strong as her earlier ones so I would definitely recommend going back. LaRose, The Plague of Doves, and The Roundhouse are three that come to mind that I enjoyed.

I'm interested to read your experience with Maryse Condé! I have wanted to read her for a while too but have never quite known where to start, so subsequently never read her! I think I will sit back and watch your Condé goal unfold until I hear of one of her novels you really (!) recommend..